The Devil Is to Blame

Once upon a time the devil was looking for the most effective weapon against God. The first demon proposed to tell people that there is no God. Another said it’s better to tell them there is no soul. The third proposal was the one the devil accepted: people should be told there is no rush.

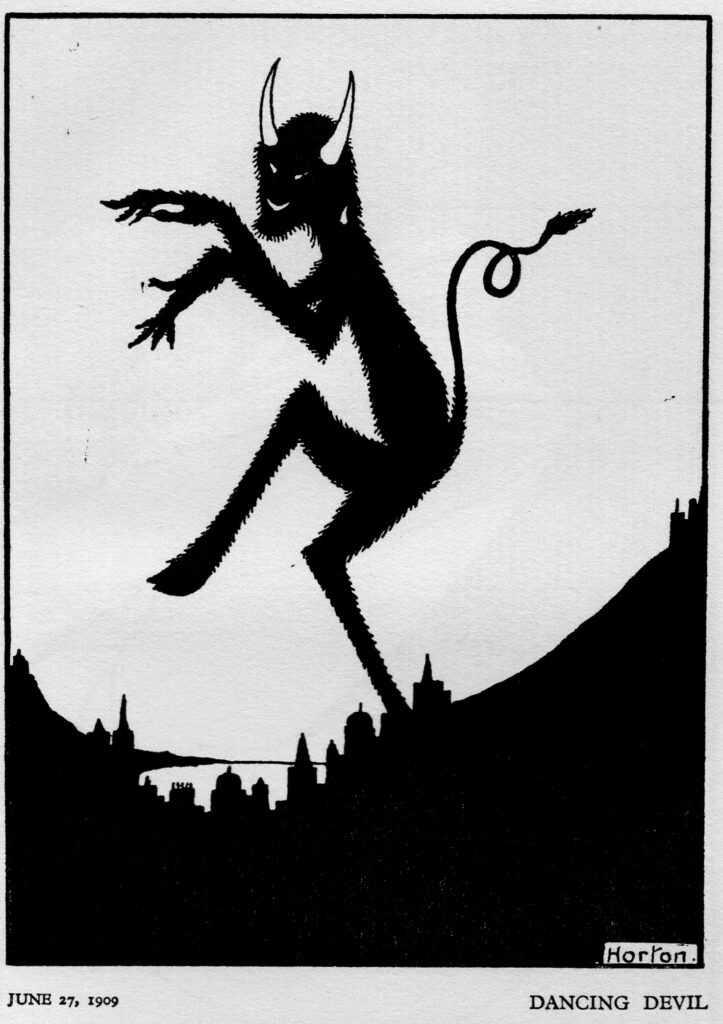

Our biggest opponent in the metamodernistic age of overabundant information is procrastination. Schopenhauer said that our existence moves like a pendulum between suffering and boredom, and we are, at the same time, tortured souls and devils to one another. A visual metaphor of this is evident in the shackled humanoid figures at the bottom of the Devil tarot card. They are discouraged and in no hurry. Above them is their master the Devil, the embodiment of vanity, ambition, and power. The card represents the diabolical extremes of our ego. All or nothing.

The artistic representation of the devil did not mature for years after the Middle Ages. The devil seems like a confused child who wants to try everything. His body is an extravagant and grotesque pile of extremities: wings, horns, breasts, claws, hooves, eyes on his belly, etc. The pentagram is a symbol of Venus, the first morning star, the planet of pleasure, perfection, and love. The horns are a symbol of divine wisdom. In Hinduism the trident was a weapon against evil, and in ancient Greece, the scepter of Poseidon, the god of the sea. All these symbols were added gradually as the church battled the pagan mythologies.

Read more

Semitic monotheistic religions based their aesthetic representations of mythology on the text of the Avesta, the holy book of Zoroastrianism, whose main characters are Ahura Mazda (god of good) fighting against Anga Mainyu (spirit of destruction). In ancient, pagan religions, or in Hinduism, we will not find such discrete expressions of the roles of good and bad. The principle of evil is opposed to the principle of good, and evil must therefore be ugly per se. Ugly itself has no definition. It is simply the opposite of the beautiful. Goethe’s Mephistopheles is a force that always intends evil but produces only good. Hindus always leave a part of the temple, such as a window, unfinished so as not to invite the evil eye. Perfectionism is a disease of the ego. “I want to know ” is the line of Irina Spalko, a scientist who aspires to get all the knowledge of the universe from the aliens in the film Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008).

The Bible would not be interesting if Adam and Eve remained knowledge free. Every good mythology must have good guys and bad guys. Conflict (agon) is the basis of every good drama. Who would watch a movie that focused only on after the characters got married and lived happily ever after? It took the serpent, who did the first successful marketing campaign in history by convincing Eve to persuade Adam to taste the forbidden fruit from the Tree of Good and Evil. By giving us knowledge, she opened the door to pairs of opposites. If the ugly is the absence of the beautiful, and the evil is necessary to perceive the good, then we have a culprit on call for all the darkness in our soul. Balashevich, one of the best Slavic songwriters, talks about our devilish instincts like this:

“… đavo mi je kriv.

On mora sve da proba …

Ne pijem što uživam, nit što mi dobro stoji. Pijem da njega napojim.

Ne lutam što uživam, nit miris druma volim. Lutam da njega umorim.

Ne sviram što uživam, nije to pesma prava. Sviram da njega uspavam.”

“… It’s the devil’s fault.

He has to taste everything …

I don’t drink because I enjoy it, nor because it fits me. I drink to feed him.

I don’t wander because I enjoy it, nor do I like the smell of the road. I wander to tire him out.

I don’t sing because I enjoy it, it’s not a real song. I sing to put him to sleep.”

The devil, as the instinctive nature of our libido, represents the grotesque side of the unconscious shadow that we project through the ego into the world around us. The devil is ambiguous by nature. He leads us to sin, but sinning gives us self-knowledge. Without the devil’s interference, we would not have free will or the opportunity to choose. We would not be able to get to know and overcome our egos. We would be animals ruled by instinct, trapped in formulas and routines of programmed obedience.

Al Pacino as John Milton, the devil in the movie The Devil’s Advocate (1997), explains himself: “I’m here on the ground with my nose in it since the whole thing began! I’ve nurtured every sensation man has been inspired to have! I cared about what he wanted, and I never judged him… I’m a fan of man! I’m a humanist. Maybe the last humanist. Who, in their right mind, Kevin, could possibly deny the twentieth century was entirely mine? All of it, Kevin! All of it! Mine! I’m peaking, Kevin. It’s my time now.” In this film, the devil is a rich businessman in an Armani suit who has his fingers in the legal system. In the twenty-first century, the Devil has extended his jurisdiction to bankers, pharmacists, the IT industry, and construction. Artists or philosophers are no longer under his clutches, as they were in the Middle Ages. Vanity is the devil’s favorite sin. He has taken over all the activities in which man wants power and perfection, and thus puts temptations before our egos.

The third chakra in the solar plexus is the Manipura chakra. The solar plexus focuses on the power and autonomy of metabolism. The element of the solar plexus is fire. Activating fire helps digest food. Manipura chakra is the center of vitality. It is also the center of projection and fear. “For the thing which I greatly feared is come upon me, and that which I was afraid of is come unto me” (KJV, Job 3:25). When this chakra is in balance, we are calm, and we have no problems with panic, worrying, overthinking, vanity, or lust for knowledge or power. This is the warrior chakra, and it is activated in the defense of individuality. The energy here can be devastating. And next to the fire, her symbol is a ram, which has horns. On the Tarot card of the Devil, a special pair of eyes is located in the place of the solar plexus. This chakra is home to the devil’s place of movement and the fiery energy of the ego. “The energy is aggressive. Conquer. Consume. Turn everything into oneself.” This is how Campbell describes this chakra. When our ego hardens so much, we get stuck with it. Hell is filled with people who are stuck with themselves.

The devil’s intentions turned against him, and he failed to control the Manipura fire in which ego and self must be rejected in order to accept both good and bad. The universe is not perfect, and the pursuit of perfection and the ambition to be the best led the devil to Hell. It’s not easy for him there, stuck between obsession and discouragement. There is a Sufi legend from Persia, in which Lucifer’s fall into hell is explained interestingly. According to Islamic tradition, there are three types of beings: angels (beings of light), jinn (beings of fire, not all of them bad or demons), and humans (beings of the earth). These three elements are what these three types of beings are made of. We humans are made of carbon, clay. When God made us, he asked that all the angels worship the clay man. Lucifer refused because he did not want to worship anyone but God, causing Campbell to say of Iblis (the Islamic name for Satan) that he was God’s greatest lover.

The devil cannot see the one he loves. He lives only on the memory of his beloved’s voice from the last time he heard it. And what does someone who has been rejected or deceived in love do? Sadness and anger turn into infernal egoism, which, with its ambition and lust for power, destroys and frightens everyone around it, trying even to destroy what its loved one loves. In this battle within the solar plexus, the wolf we feed more wins. One is evil and the other represents joy, peace, self-awareness, gratitude, empathy, truth, and love. (The parable of the two wolves occurs in Cherokee Indian culture as well as in Zen Buddhism.) At the end of the story, we should thank the devil. Without him we would not have fought the battles in our lives and come to know good, truth, or love.

The experience of life is the greatest gift that we should not ignore. We have two options: to do nothing, like the chained figures at the bottom of the map, or to do it all, like the devil himself. No special meaning should be sought in this. As Campbell says: “Life has no meaning. Each of us has meaning and we bring it to life … I think that what we’re seeking is an experience of being alive, so that our life experiences on the purely physical plane will have resonances with our own innermost being and reality, so that we actually feel the rapture of being alive.”

Campbell is on the same page with Sadghuru’s teaching that life is an experience to be fully lived. What we should seek is the rapture of the experience of life, not waiting for it to happen but actively participating in all the dark and light parts of our soul. And as for the bad, dark, and ugly expressions of human nature, we no longer need a scapegoat. We no longer need to say the devil is to blame, the devil made me do it. Our devils are inside us, and that is a great realization. From that perspective, we have much more influence and authority over our own lives.

Dr. Lejla Panjeta is Professor of Film Studies and Visual Communication. She was professor and

guest lecturer in many international and Bosnian universities. She also directed and produced in theatre, worked in film production, and authored documentary films. She curated university exhibitions and film projects. She won awards for her artistic and academic works. She is the author and editor of books on film studies, art, and communication. Her recent publication was the bilingual illustrated encyclopedic guide – Filmbook, made for everyone from 8 to 108 years old. Her research interests are in the fields of aesthetics, propaganda, communication, visual arts, cultural and film studies, and mythology. https://independent.academia.edu/LejlaPanjeta

Dr. Lejla Panjeta is Professor of Film Studies and Visual Communication. She was professor and

guest lecturer in many international and Bosnian universities. She also directed and produced in theatre, worked in film production, and authored documentary films. She curated university exhibitions and film projects. She won awards for her artistic and academic works. She is the author and editor of books on film studies, art, and communication. Her recent publication was the bilingual illustrated encyclopedic guide – Filmbook, made for everyone from 8 to 108 years old. Her research interests are in the fields of aesthetics, propaganda, communication, visual arts, cultural and film studies, and mythology. https://independent.academia.edu/LejlaPanjeta

Weekly Quote

In other traditions, good and evil are relative to the position in which you are standing. What is good for one is evil for the other. And you play your part, not withdrawing from the world when you realize how horrible it is, but seeing that this horror is simply the foreground of a wonder: a ‘mysterium tremendum et fascinans.’

Featured Video

News & Updates

In this episode, Tyler Lapkin of the Joseph Campbell Foundation sits down with Andrew McCarthy. Andrew McCarthy is an actor, director, and award winning travel writer. He has walked the Camino De Santiago in Spain, not once but twice, and he chronicles his second Camino with his son, in his most recent book, Walking With Sam. He has appeared in dozens of films, including such iconic movies as Pretty in Pink, St. Elmo’s Fire, Less Than Zero, Weekend At Bernie’s and Mannequin. Andrew has directed nearly a hundred hours of television, including The Blacklist, Grace and Frankie, New Amsterdam, Orange is the New Black, and many others. For a dozen years Andrew served as an editor-at-large with National Geographic Traveler magazine. He has written for The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Los Angeles Times, The Atlantic, Time, and many others. In addition to Walking with Sam, he is the author of The Longest Way Home, Brat, and Just Fly Away, In the conversation, we delve deep into his experiences on the Camino, the meaning of pilgrimage, the wisdom he has gained from his walks, and the resonance of Joseph Campbell’s teachings in his own personal journey. For more information about Andrew, visit his website: https://andrewmccarthy.com/

Featured Work

Toward a Natural History of the Gods and Heroes (eSingle)

The exciting prologue to Primitive Mythology

The comparative study of the mythologies of the world compels us to view the cultural history of mankind as a unit; for we find that such themes as the fire-theft, deluge, land of the dead, virgin birth, and resurrected hero have a worldwide distribution — appearing everywhere in new combinations while remaining, like the elements of a kaleidoscope, only a few and always the same.

Where The Hero with a Thousand Faces looks at the universal themes of myths and dreams, in the four books of his great Masks of God series Joseph Campbell explores the ways in which those themes have varied across the ages and between cultures. Yet in this full-throated introduction, Campbell establishes his basic thesis: that although humanity’s myths are many, their source is “always the same.”

Subscribe to JCF’s email list to receive a weekly MythBlast newsletter along with occasional news and special offers from JCF.