Dynamics of the Diabolic

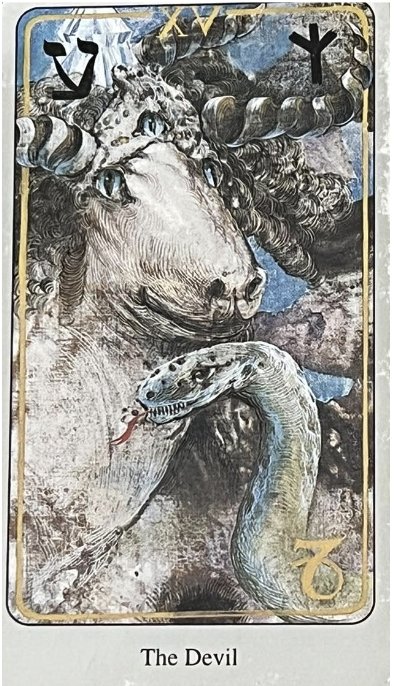

Our MythBlast essay series continues to explore the archetypal imagery of the tarot, focusing this month on Card XV in the major arcana: the Devil.

For almost two thousand years those who practice the occult arts have been portrayed as dabbling in the demonic. We all know the story from countless variations in book and film: even those who display innocent curiosity are depicted as opening themselves to satanic influences, which never end well. From Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors in 1965 to television’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer, drawing the Devil card sets a sinister tone.

And small wonder: in Christian dogma the devil is considered summum malam, the highest or supreme evil.

But is this what the Devil signifies in tarot––portents of evil? Or is there more nuance to this mythic figure? How the devil did the devil become the Devil?

Surprisingly, there is no identification in Hebrew scriptures of the devil with the talking serpent tempting Eve in the Garden. Similarly, the only mention of “Lucifer” (“shining one” or “light bearer”) in the Jewish canon appears to be an allegorical reference to the king of Babylon (Isaiah 14:4–23), though this passage is later taken by Christians (but not Jews) as a veiled account of the devil’s origin.

Read more

Nor is “Satan” the devil’s name. The Hebrew word śāṭān means “accuser” or “adversary,” and is so translated to describe a number of figures—from King David (in I Samuel 29:4, where the Philistines fear he will become their adversary) to an “angel of the Lord” who blocks the sorcerer Balaam’s way (Numbers 22:22).

However, when used with the definite article (ha-śāṭān: “the Satan”), which occurs only in the Old Testament books of Job and Zechariah, it’s a title applied to a member of God’s heavenly court who serves a prosecutorial role. At this stage of his evolution, Satan appears to be a spirit being who reports directly to God in heaven, does God’s bidding, and even indulges in a gentleman’s wager of sorts with the deity; this figure is no fallen angel residing in hell, nor is he at war with God––and he is definitely not the source of evil.

That role is reserved for the God of Israel, who declares, in Isaiah 45:7, “I form the light, and create darkness; I make peace, and create evil: I the Lord do all these things” (KJV).

And He does. Whenever Pharaoh is on the point of agreeing to the Lord’s demand to allow the Israelite slaves to leave, it is God, not the devil, who hardens Pharaoh’s heart, compounding the suffering of Hebrews and Egyptians alike (Exodus 7:13; 9:12; 10:20; 10:27; 14:4). It is God, not the devil, who sends an evil spirit to torment King Saul (I Samuel 16:14). And when Israel’s King Ahab seeks to know the will of God, Ahab is killed in battle because “the Lord hath put a lying spirit” in the mouths of the prophets (I Kings 22: 5–23).

The figure of Satan as the epitome of evil, in perpetual conflict with a God who is only righteous and pure and good, doesn’t emerge until the period of the Babylonian captivity. After sacking Jerusalem, in 597 BCE, Nebuchadnezzar II forcibly deports the bulk of the Jewish religious leadership and nobility to Babylon, where they and their descendants remain in exile for the next sixty years. Cyrus the Great, founder of the Achaemenid (aka Persian) Empire, eventually defeats the Babylonians and allows the Jews to return to Jerusalem.

Thanks to cross-fertilization with Zoroastrianism, the dominant religion in the Persian empire, the exiles bring with them new ideas:

Now there were two extremely important innovations that transformed the mythologies of the Levant and that then very soon affected Europe. One came along with the rise of Zoroastrianism, where the principles of light and darkness are separated from each other absolutely and the idea is developed of two contending creative deities . . . absolute good and absolute evil. There is in the earlier traditions no such dualistic separation of powers, and we in our own thinking have inherited something of this dualism of Good and Evil, God and Devil, from the Persians.

(The Mythic Dimension, p. 256-257)

With this movement, the figure of Satan morphs into the devil we know today––but in the Christian era the conceptualization of the deity also undergoes a transformation.

In most other belief systems, the adversary/trickster figure is not wholly evil––even Loki has his moments––but in Christianity, as in Zoroastrianism, God is conceived of as the ultimate source of all that is Good, and only Good . . . and pure good, pure light, casts a dark and monstrous shadow. If God is only Good, then his shadow, everything that God isn’t, must be utter Evil.

You cannot have light without the shadow; the shadow is the reflex of the figure of light.

(Thou Art That, p. 75)

According to Jungian psychology, the shadow is frequently related to one’s personal unconscious, which is called the unconscious not because it is unconscious and without purpose but because the waking ego (“me,” “I”, how I perceive myself) is unconscious of these deeper parts of the psyche:

The shadow is, so to say, the blind spot in your nature. It’s that which you won’t look at about yourself . . . The shadow is that which you might have been had you been born on the other side of the tracks: the other person, the other you. It is made up of the desires and ideas within you that you are repressing—all of the introjected id. The shadow is the landfill of the self. Yet it is also a sort of vault: it holds great, unrealized potentialities within you.

The nature of your shadow is a function of the nature of your ego. It is the backside of your light side.

(Pathways to Bliss, p. 73)

Shadow contents, those unknown or repressed parts of one’s being, are experienced as threatening to waking ego. Rather than accept these shadow traits as part of oneself, we tend to project shadow contents outside ourselves, onto those who have hooks in their personality, on which those projections might catch and snag, thus allowing us to evade self-loathing and self-knowledge, by directing fear and hatred outward, onto some “Other.”

Is it coincidence that God instructs Moses, “Thus shalt thou say unto the children of Israel, I AM hath sent me to you” (Exodus 3:14)? Certainly, “I AM THAT I AM”––the name of the deity in the Judeo-Christian tradition––has been interpreted as a statement having profound theological implications; at the same time, at least on the surface, it sure sounds like a declaration of ego. And if that divine ego identifies itself only with all things good, then all things evil fall into shadow, which is projected outward onto the gods of others, who are then considered to be devils.

In this mythological context the idea of the occult, as black magic, becomes associated with all of the religious arts of the traditional pagan world, and the very symbols of such gods as Śiva and Poseidon, for example, become symbolic of the devil. The trident of Śiva and Poseidon and the pitchfork of our devil are the same. Moreover, there now begins to become associated with the occult a new tone, one of fearful danger, diabolical possession, and so forth, and what formerly was daemonic possession—possession by a god such as Dionysus—becomes evil: a new mythology of warlocks and witches, pacts with the devil, and so forth, comes into being.But there is an earlier mythological law that tells that when a deity is suppressed and misinterpreted in this way, not recognized as a deity, he indeed may become a devil. When the natural impulses of one’s life are repressed, they become increasingly threatening, violent, terrible, and there is a furious fever of possession that then may overtake people; and many of the horrors of our European Christian history may be interpreted as the results of this natural law.”

(The Mythic Dimension, p. 258)

And so, we come full circle, back to “the idea of the occult,” specifically, the Devil in the major arcana. This card signifies evil primarily to those unfamiliar with tarot. But there is another way to interpret this image:

What is the obstruction in your life, and how do you transform it into the radiance? Ask yourself, “What is the main obstruction to my path?” . . . A demon or devil is a power in you to which you have not given expression, an unrecognized or suppressed god.

(A Joseph Campbell Companion, p. 156)

That’s worth repeating: a “devil is a power in you to which you have not given expression.” By becoming aware of and giving expression to what has been unconscious, we disempower the shadow’s ability to disrupt our lives.

[T]he attitude that Joyce has in his work is not that of withdrawing but affirming; yet in the affirmation, having lined up on one side, you are not to identify yourself with God and the other side with the Devil; the two represent a polarity. Or if you do identify yourself with God and the other with the Devil, then you must realize that there is a higher principle, higher than the duality of God and Devil of which they themselves are the polarized aspects.

(Mythic Worlds, Modern Words, p. 271)

When I draw the Devil in a tarot spread, I do not take the card as evil. Rather, for me, it’s a reminder to seek out what I have ignored, repressed, or overlooked in my life––which takes honest and often challenging self-reflection––and then embrace it.

The path to wholeness begins with owning one’s own shadow. As Joseph Campbell often noted, citing Nietzsche, “Be careful lest in casting out your Devil you cast out the best that is in you” (Asian Journals, p. 221).

Maybe it’s time we give the devil his due . . .

Stephen Gerringer has been a Working Associate at the Joseph Campbell Foundation (JCF) since 2004. His post-college career trajectory interrupted when a major health crisis prompted a deep inward turn, Stephen “dropped out” and spent most of the next decade on the road, thumbing his away across the country on his own hero quest. Stephen did eventually “drop back in,” accepting a position teaching English and Literature in junior high school.

Stephen Gerringer has been a Working Associate at the Joseph Campbell Foundation (JCF) since 2004. His post-college career trajectory interrupted when a major health crisis prompted a deep inward turn, Stephen “dropped out” and spent most of the next decade on the road, thumbing his away across the country on his own hero quest. Stephen did eventually “drop back in,” accepting a position teaching English and Literature in junior high school.

Weekly Quote

My definition of a devil is a god who has not been recognized. That is to say, it is a power in you to which you have not given expression, and you push it back. And then, like all repressed energy, it builds up and becomes completely dangerous to the position you’re trying to hold.

Featured Video

News & Updates

In this episode, Tyler Lapkin of the Joseph Campbell Foundation sits down with Cory Sandhagen. Cory is an American professional mixed martial artist. He currently competes in the Bantam weight division in the Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC). With a background in psychology and a deep appreciation for the insights of visionaries like Carl Jung, Krishnamurti, and Joseph Campbell, Sandhagen has delved into the depths of the human psyche, exploring the transformative power of facing fears head-on.

Sandhagen’s path is a testament to the idea that true strength is not merely physical, but also mental and emotional. By venturing into the realm of the unknown, he embodies the hero’s journey, taking us on a captivating exploration of how confronting our fears can lead to profound self-discovery and empowerment.

Featured Work

Toward a Natural History of the Gods and Heroes (eSingle)

The exciting prologue to Primitive Mythology

The comparative study of the mythologies of the world compels us to view the cultural history of mankind as a unit; for we find that such themes as the fire-theft, deluge, land of the dead, virgin birth, and resurrected hero have a worldwide distribution — appearing everywhere in new combinations while remaining, like the elements of a kaleidoscope, only a few and always the same.

Where The Hero with a Thousand Faces looks at the universal themes of myths and dreams, in the four books of his great Masks of God series Joseph Campbell explores the ways in which those themes have varied across the ages and between cultures. Yet in this full-throated introduction, Campbell establishes his basic thesis: that although humanity’s myths are many, their source is “always the same.”

Subscribe to JCF’s email list to receive a weekly MythBlast newsletter along with occasional news and special offers from JCF.